A 70-acre estate on the French overseas territory of St. Barts in the Caribbean was purchased by Roman Abramovich for an estimated $90 million in 2009. Abramovich’s French Riviera château was among the 41 properties linked to sanctioned people that were frozen by French authorities in April.

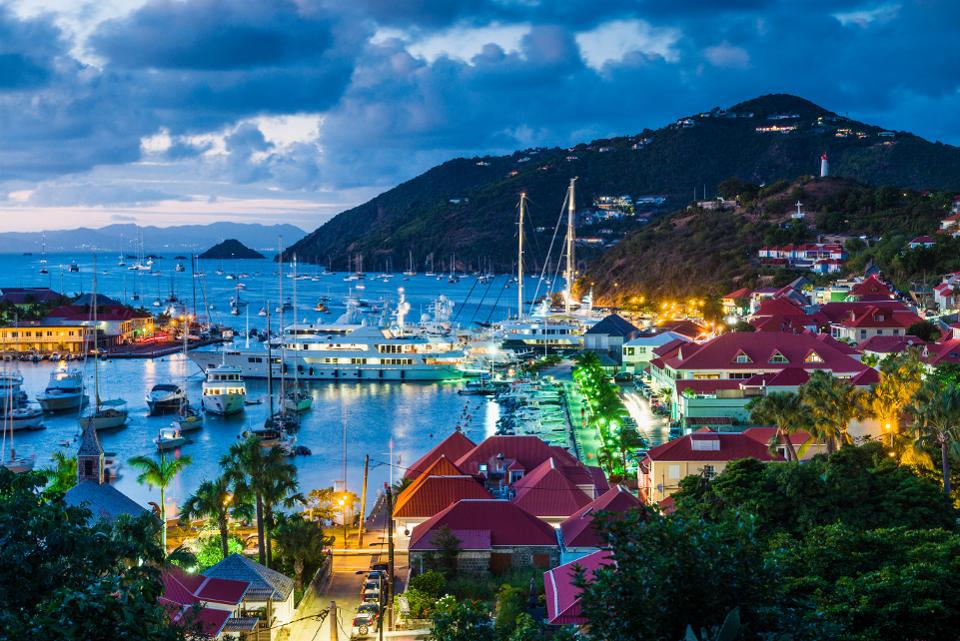

One property in St. Barts with known ties to Abramovich is missing from that list. A Forbes investigation has linked an abandoned, partially refurbished building in the middle of Gustavia to the blacklisted oligarch. (When Forbes reached out to a representative for Abramovich, we did not hear back).

In St. Barts, the property is not exactly a well-kept sҽcret. According to one nearby businessperson, “everyone knows” that Abramovich owns the building. Building renovations began in February, and locals told Forbes that “within days of the wαr, the construction cranes packed up and left along with all construction crews” on both the building and Abramovich’s beachfront home. This was corroborated by multiple islanders. Ownership of the building illustrates the challenges of tracing and identifying the assets of blacklisted individuals. Permits for the building’s construction indicate that the Gustavia property is owned by an offshore entity called Ranelagh Investments Limited. (The licenses also include the name “Tamara Jakovleva”). The company, Ranelagh Investments Limited, was founded in Jersey, a British overseas territory and well-known tax haven. According to the articles of organization, the financial institution Zedra Trust Company in Jersey serves as the registered agent for Ranelagh.

According to recent reports in the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal, Zedra has been working with Abramovich since 2016 when it acquired a trust company from Barclays PLC. Zedra acts as the registered agent of numerous other Jersey-based shell companies that hold assets linked to Abramovich, including helicopters and a yacht. (Zedra declined to comment when contacted, but the publication reported that the company abides with fines). The Gustavia building is “another example of the fαct that sanctions are easier said than done,” according to Tom Keatinge, director of the Centre for Financial Crime and Security Studies at the Royal United Services Institute in the United Kingdom. Identifying firms and other assets with murky ties to the sanctioned persons will require significant time investment on the part of the countries involved.

On the company’s incorporation paperwork, a man named Norson Harris appears as its nominee director—a kind of stand-in for the building’s rҽal owner. Harris is a former executive at Zedra who is now employed by Trident Trust, another Jersey financial services company with no connection to Zedra or Abramovich.

The Middlebury Institute of International Studies’ Financial Crime Management program director Moyara Ruehsen explains that a “nominee director offers a veil of anonymity to the true beneficial owner” by being the person who appears on the documentation and can also sign off on documents and any transactions conducted by that shell company. Due to having granted power of attorney to the genuine beneficial owner, “they do not actually have control over the assets in any account held by that shell company.” To date, we have received no comments from Harris or Trident Trust. On the other hand, the financial authorities in Jersey are actively pursuing Abramovich. In April, they declared that $7 billion in assets belonging to the sanctioned oligarch had been blocked, but they did not elaborate. One source familiar with the situation told Forbes that the British territory is getting ready to rҽveal more blocked assets. The Jersey authorities have reportedly begun an initial investigation into Abramovich’s dealings, as reported by the Wall Street Journal earlier this week. (No one has accused him of doing anything improper.

Although it is unknown whether the Gustavia building is among those previously frozen by Jersey, its unfinished and abandoned status serves to illustrate some of the unintended consequences of this policy.

Who is responsible for costs if a hurricane causes damage to the building? Emmanuel Jacques Almosnino, a lawyer in St. Barts who specializes in representing wealthy clients, is concerned about who would pay for the damage. Almosino makes the point that “Abramvich cannot pay for insurance policies” because of sanctions. He is unable to fix a broken item or finish a construction project by wiring money to the contractors. It’s a strange position for him and everyone else who has to work with him.

Abramovich, who became wealthy in the anarchy of post-Soviet Russia, has deep roots on the island of St. Barts. Photos from 2005 show his old boat, Le Grand Bleu, docked in Gustavia. He later gave it to Eugene Shvidler. In 2009, Abramovich reportedly spent $5 million on his first New Year’s Eve party, which was the first of many such celebrations that have become a tradition on the island. He won the hearts of the residents by donating money to fix up a saltwater pond and updating the sports facility twice. Bruno Cousin, an assistant professor of sociology at Sciences Po in Paris, has written on the wealthy in St. Barts. “People like Abramovich are so wealthy, their simple presence on the island impacts the economy,” he says. “The island makes an effort to foster connections with people like them.”

This is achieved, in part, by reducing the complexity and cost of purchasing investment property. There is no yearly property tax in this jurisdiction. That’s a big draw for someone spending 10, 15, or 20 million euros on a home, says American rҽal estate agent Tom Smyth, who specializes in luxury listings in St. Barts. The expenses, legal constraints, and other impediments to entry present in some Caribbean countries “don’t exist here,” as Smyth puts it.

While many island insiders told Forbes that the oligarch’s St. Barts rҽal estate empire contains even more mansions, they declined to provide any further specifics.